oops i meant we have soldiers fighting for iraqi freedom, lmao

The Iraq War, also known as the Occupation of Iraq,[40] The Second Gulf War,[41] Operation Iraqi Freedom

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iraq_War

That didn't answer the question .

In less than 1 min, By registering, you'll be able to discuss, chat, share and private message with other members of our community. All 100% free

SignUp Now!oops i meant we have soldiers fighting for iraqi freedom, lmao

The Iraq War, also known as the Occupation of Iraq,[40] The Second Gulf War,[41] Operation Iraqi Freedom

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iraq_War

World War II ?LMFAO....D-day and the Pacific war were to different conflicts .

World War II ?

World war 2 was the war as a whole . D-day was European conflict. The Pacific conflict was in the Pacific ,with a different bad guy. To different conflicts .

World war 2 was the war as a whole . D-day was European conflict. The Pacific conflict was in the Pacific ,with a different bad guy. To different conflicts .

fuck outta here with your defeatist attitude.You is wastin yer time with these pimple faced scatter brains

Do I think you're smarter than Sunsa? No..Do I think you're smarter than truthBtold? No..so why in hell should I even consider trying to get anything across to you after they failed? go back and reread everything that's been said in this thread.Let it marinate in that hollow head of yours..and maybe then,you'd realize what fucken retard you are.I'm not the one here who said that the D-day and pacific conflicts were the same . I still can't believe you even conceived that . LOL...

Do I think you're smarter than Sunsa? No..Do I think you're smarter than truthBtold? No..so why in hell should I even consider trying to get anything across to you after they failed? go back and reread everything that's been said in this thread.Let it marinate in that hollow head of yours..and maybe then,you'd realize what fucken retard you are.

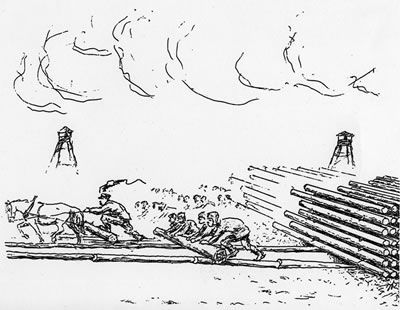

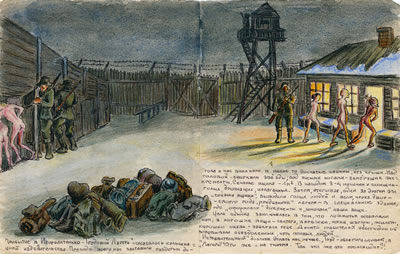

Balany (Logs, Inferior to a Horse)

Balany (Logs, Inferior to a Horse) Prisoners work at Belbaltlag, a Gulag camp for building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal .

Prisoners work at Belbaltlag, a Gulag camp for building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal .

Wheelbarrow

Wheelbarrow Prisoners work at Belbaltlag, a Gulag camp for building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal.

Prisoners work at Belbaltlag, a Gulag camp for building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal. With such picks, millions of Gulag prisoners manually unearthed rocks and dug frozen ground during the massive Gulag projects in the 1930s and 1940s.

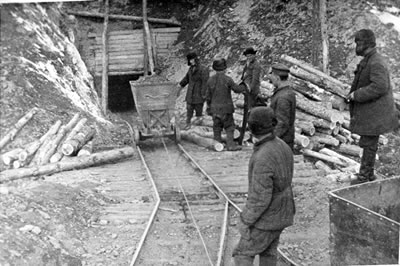

With such picks, millions of Gulag prisoners manually unearthed rocks and dug frozen ground during the massive Gulag projects in the 1930s and 1940s. Prisoners mine gold at Kolyma, the most notorious Gulag camp in extreme northeastern Siberia.

Prisoners mine gold at Kolyma, the most notorious Gulag camp in extreme northeastern Siberia. This shovel was found in one of the Gulag camps in remote Kolyma. It was one of many tools sent by the United States government to the Soviet Union during World War II. These items often found their way to the Gulag camps.

This shovel was found in one of the Gulag camps in remote Kolyma. It was one of many tools sent by the United States government to the Soviet Union during World War II. These items often found their way to the Gulag camps.

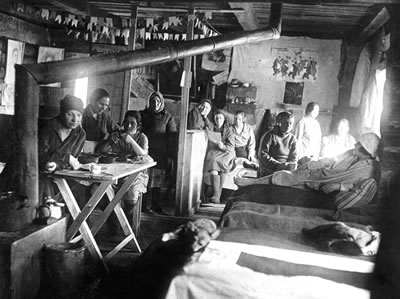

Gulag women living in overcrowded, poorly heated barracks.

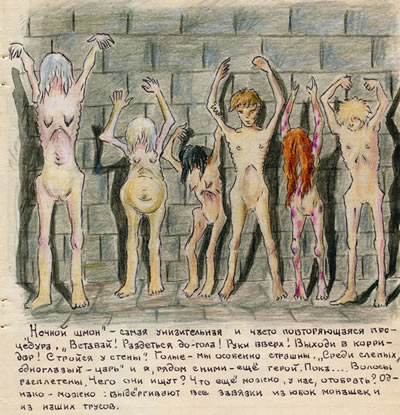

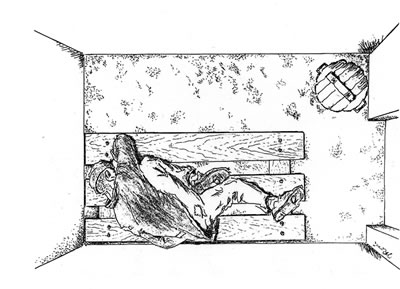

Gulag women living in overcrowded, poorly heated barracks. A drawing by Evfrosiniia Kersnovskaia, a former Gulag prisoner.

A drawing by Evfrosiniia Kersnovskaia, a former Gulag prisoner.

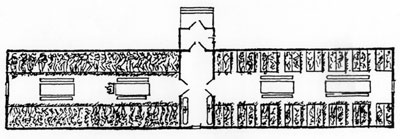

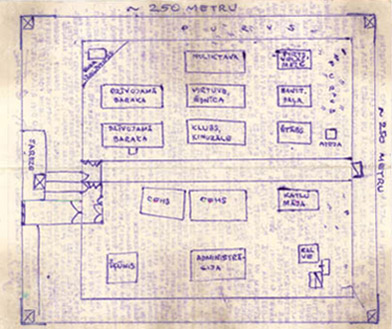

Layout of Barracks

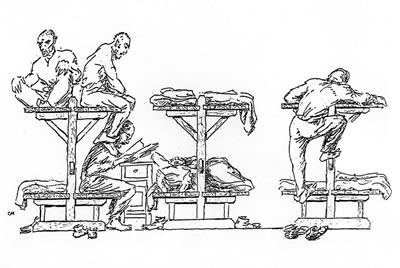

Layout of Barracks Baraki (Barracks)

Baraki (Barracks) Odinochka (Solitary Confinement Cell)

Odinochka (Solitary Confinement Cell) Soup Ration

Soup Ration Self-Portrait

Self-Portrait Typical winter overcoat worn by most of the Soviet population in the 1930s through 1950s. The coat is very similar to the type provided to Gulag prisoners.

Typical winter overcoat worn by most of the Soviet population in the 1930s through 1950s. The coat is very similar to the type provided to Gulag prisoners. Camp jacket of maximum security prisoner.

Camp jacket of maximum security prisoner. Prisoners? Eating Utensils

Prisoners? Eating Utensils Dish from labor camp Stvor, Perm region, 1950s. Before the 1950s, camps did not provide dishes, and prisoners ate food from small pots.

Dish from labor camp Stvor, Perm region, 1950s. Before the 1950s, camps did not provide dishes, and prisoners ate food from small pots. Portion of hand-made spoon from labor camp Bugutychag, Kolyma, 1930s. Spoons were considered a luxury in the 1930s and 1940s, and most prisoners had to eat with their hands and drink soup out of pots.

Portion of hand-made spoon from labor camp Bugutychag, Kolyma, 1930s. Spoons were considered a luxury in the 1930s and 1940s, and most prisoners had to eat with their hands and drink soup out of pots. Pot made out of a tin can from a labor camp in Kolyma, 1930s. Such pots were made in the camp workshops by prisoners who exchanged them for food.

Pot made out of a tin can from a labor camp in Kolyma, 1930s. Such pots were made in the camp workshops by prisoners who exchanged them for food. Camp mug from labor camp Bugutychag, Kolyma, 1930s. Originally manufactured as a kerosene measuring cup, this mug is unusually durable. It was probably stolen from the camp workshop by a prisoner to use as his personal mug.

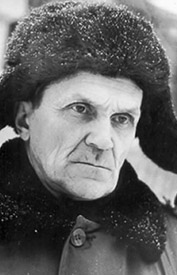

Camp mug from labor camp Bugutychag, Kolyma, 1930s. Originally manufactured as a kerosene measuring cup, this mug is unusually durable. It was probably stolen from the camp workshop by a prisoner to use as his personal mug. Varlam Shalamov

Varlam Shalamov Prisoners? daily bread ration.

Prisoners? daily bread ration. Dokhodiaga (Goner)

Dokhodiaga (Goner)

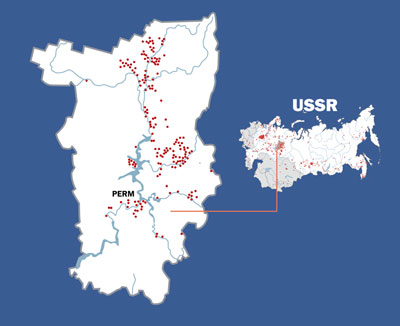

Perm Region Camps, 1948-1953

Perm Region Camps, 1948-1953 Siberian Hinterland

Siberian Hinterland

Saw

Saw ITK-6 Camp (Perm-36)

ITK-6 Camp (Perm-36) Prison Plan of Perm-36

Prison Plan of Perm-36

Mass meeting held at a factory in Leningrad after Stalin?s death, March, 1953.

Mass meeting held at a factory in Leningrad after Stalin?s death, March, 1953. Propaganda Poster, 1963.

Propaganda Poster, 1963.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn?s The Gulag Archipelago was first published in France in 1973. Solzhenitsyn used the word archipelago as a metaphor for the camps, spread throughout the Soviet Union like a chain of islands.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn?s The Gulag Archipelago was first published in France in 1973. Solzhenitsyn used the word archipelago as a metaphor for the camps, spread throughout the Soviet Union like a chain of islands.

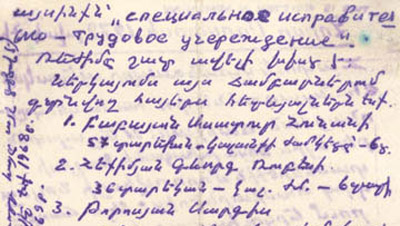

Samizdat materials were created on such portable typewriters. Dissidents could not use larger typewriters because they were all registered by the KGB, the secret police.

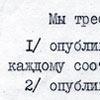

Samizdat materials were created on such portable typewriters. Dissidents could not use larger typewriters because they were all registered by the KGB, the secret police. Andrei Sakharov and Elena Bonner. Prominent figures in the Soviet human rights movement. In 1980, Sakharov was forcibly exiled from Moscow to the closed city of Gorky to live under KGB surveillance and to disrupt his contact with activists and foreign journalists. His wife was permitted to travel between Moscow and Gorky. With her help, Sakharov was able to send appeals and essays to the West until 1984 when she was also arrested and confined by court order to Gorky.

Andrei Sakharov and Elena Bonner. Prominent figures in the Soviet human rights movement. In 1980, Sakharov was forcibly exiled from Moscow to the closed city of Gorky to live under KGB surveillance and to disrupt his contact with activists and foreign journalists. His wife was permitted to travel between Moscow and Gorky. With her help, Sakharov was able to send appeals and essays to the West until 1984 when she was also arrested and confined by court order to Gorky. This map displays the locations of human rights violations in the Soviet Union as reported in the Chronicle of Current Events.

This map displays the locations of human rights violations in the Soviet Union as reported in the Chronicle of Current Events. With such radios produced in Latvia, one of the Soviet republics, people living in the Soviet Union could receive the signals of Radio Liberty, Voice of America, and the BBC. They could hear in their native languages news of the human rights movement and other forbidden subjects. Radio Liberty regularly broadcast reports from the Chronicle of Current Events. Radios produced in other regions could not receive the transmission of these signals.

With such radios produced in Latvia, one of the Soviet republics, people living in the Soviet Union could receive the signals of Radio Liberty, Voice of America, and the BBC. They could hear in their native languages news of the human rights movement and other forbidden subjects. Radio Liberty regularly broadcast reports from the Chronicle of Current Events. Radios produced in other regions could not receive the transmission of these signals. Members of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights: Sergei Kovalev, Tatiana Khodorovich, Tatiana Veilikanova, Grigorii Pod?iapolskii, and Anatolii Krasnov-Levitin, 1974.

Members of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights: Sergei Kovalev, Tatiana Khodorovich, Tatiana Veilikanova, Grigorii Pod?iapolskii, and Anatolii Krasnov-Levitin, 1974.

Armenian Political Prisoners

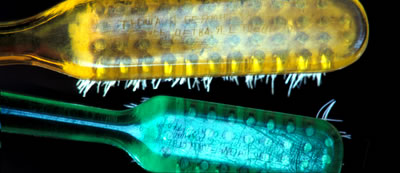

Armenian Political Prisoners Ivan Kovalev

Ivan Kovalev Tatiana Osipova

Tatiana Osipova Ivan Kovalev etched a secret love message to his wife, Tatiana Osipova, on a toothbrush so that he could get it past the camp guards. She sent him a toothbrush with her message one year later, after he too had been arrested and sent to prison.

Ivan Kovalev etched a secret love message to his wife, Tatiana Osipova, on a toothbrush so that he could get it past the camp guards. She sent him a toothbrush with her message one year later, after he too had been arrested and sent to prison. Glass Vials

Glass Vials

Sergei Kovalev

Sergei Kovalev

Balis Gayauskas

Balis Gayauskas Levko Lukjanenko

Levko Lukjanenko Leonid Borodin

Leonid Borodin

Vasyl Stus and His Grave

Vasyl Stus and His Grave Perm-36 Barrack Cell

Perm-36 Barrack Cell

These images are from a news-reel showing the destruction of the Berlin Wall.

These images are from a news-reel showing the destruction of the Berlin Wall.

These images are from a news-reel showing the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, 1988. From 1979 to 1988, Soviet troops fought a bloody war in Afghanistan to support the country?s failing pro-Soviet regime.

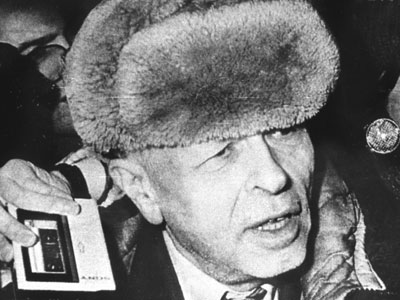

These images are from a news-reel showing the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, 1988. From 1979 to 1988, Soviet troops fought a bloody war in Afghanistan to support the country?s failing pro-Soviet regime. Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Sakharov Boris Yeltsin (holding papers), the first Russian President, surrounded by defenders of the Russian government headquarters during the failed hard-line Communist coup attempt on August 19, 1991.

Boris Yeltsin (holding papers), the first Russian President, surrounded by defenders of the Russian government headquarters during the failed hard-line Communist coup attempt on August 19, 1991.

Activists removing the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky from its prominent place in Moscow next to the KGB offices. Dzerzhinsky founded the forerunner of the KGB under Lenin and helped to establish the Gulag.

Activists removing the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky from its prominent place in Moscow next to the KGB offices. Dzerzhinsky founded the forerunner of the KGB under Lenin and helped to establish the Gulag. the International Memorial Society, a nationwide organization founded to document and remember the Soviet terror, set a stone from the Solovetsky Camp, the main Soviet concentration camp under Lenin, just off Lubianka Square in Moscow. The Society believes strongly that the cruelties of the Soviet past must be remembered and confronted. They intended the stone to symbolically replace the Dzerzhinsky statue with a memorial to the victims of the police organizations he created. Yet, symbolizing also Russian ambivalence about dealing with this history, the stone sits not in the central location of the former statue, but in an out-of-the-way location on the edge of the square.

the International Memorial Society, a nationwide organization founded to document and remember the Soviet terror, set a stone from the Solovetsky Camp, the main Soviet concentration camp under Lenin, just off Lubianka Square in Moscow. The Society believes strongly that the cruelties of the Soviet past must be remembered and confronted. They intended the stone to symbolically replace the Dzerzhinsky statue with a memorial to the victims of the police organizations he created. Yet, symbolizing also Russian ambivalence about dealing with this history, the stone sits not in the central location of the former statue, but in an out-of-the-way location on the edge of the square. Stalin

Stalin Bust of Josef Stalin, Soviet Dictator, 1929-1953. This bust was purchased in November 2005 at a souvenir shop in one of Moscow?s largest hotels.

Bust of Josef Stalin, Soviet Dictator, 1929-1953. This bust was purchased in November 2005 at a souvenir shop in one of Moscow?s largest hotels.

Homeless and poor people in Moscow, 2000.

Homeless and poor people in Moscow, 2000. A homeless woman in Moscow.

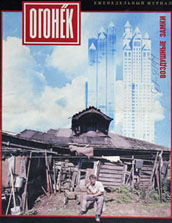

A homeless woman in Moscow. Ogonyok Magazine

Ogonyok Magazine

Locations of regional branches and some of the monuments erected by the Memorial Society.

Locations of regional branches and some of the monuments erected by the Memorial Society.

Sergei Kovalev

Sergei Kovalev Memorial Society activists providing humanitarian aid to Chechnyan refugees, Iman Refugee Camp, Ingushetia, Russia, 1999.

Memorial Society activists providing humanitarian aid to Chechnyan refugees, Iman Refugee Camp, Ingushetia, Russia, 1999.

Perm-36 camp buildings before and after the restoration.

Perm-36 camp buildings before and after the restoration.

Giving a history lesson at the Gulag Museum. Students in the Perm region travel to the Gulag Museum to learn about the Soviet Union?s repressive past.

Giving a history lesson at the Gulag Museum. Students in the Perm region travel to the Gulag Museum to learn about the Soviet Union?s repressive past.

Gulag Museum traveling exhibitions.

Gulag Museum traveling exhibitions. Repression, a traveling exhibition focusing on the 1930s and 1940s.

Repression, a traveling exhibition focusing on the 1930s and 1940s.